“It can’t have been experienced by a single person,” my grandmother sums up in a video interview she gave to Moses Mendelssohn Center in the mid-1990s.

I have often heard her say this sentence. My grandmother was one of the few Holocaust survivors who were able and willing to talk about it. With her children and even more with her grandchildren. So there was a lot that was not new to me, which she told historians as well as many young people, up to a ripe old age.

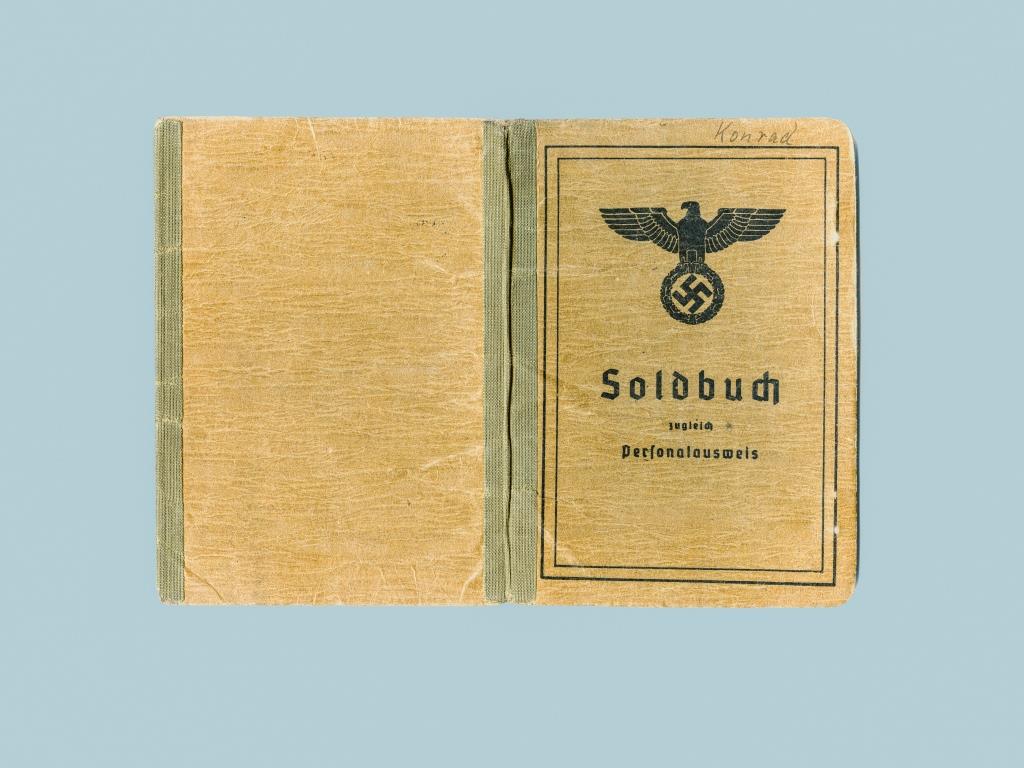

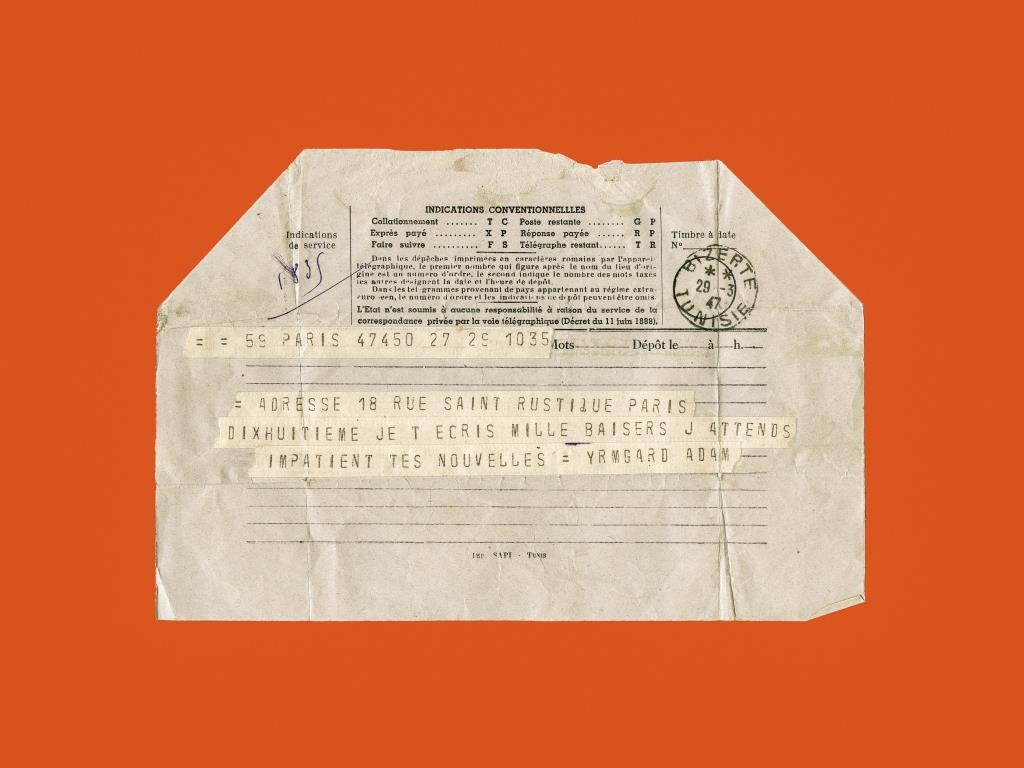

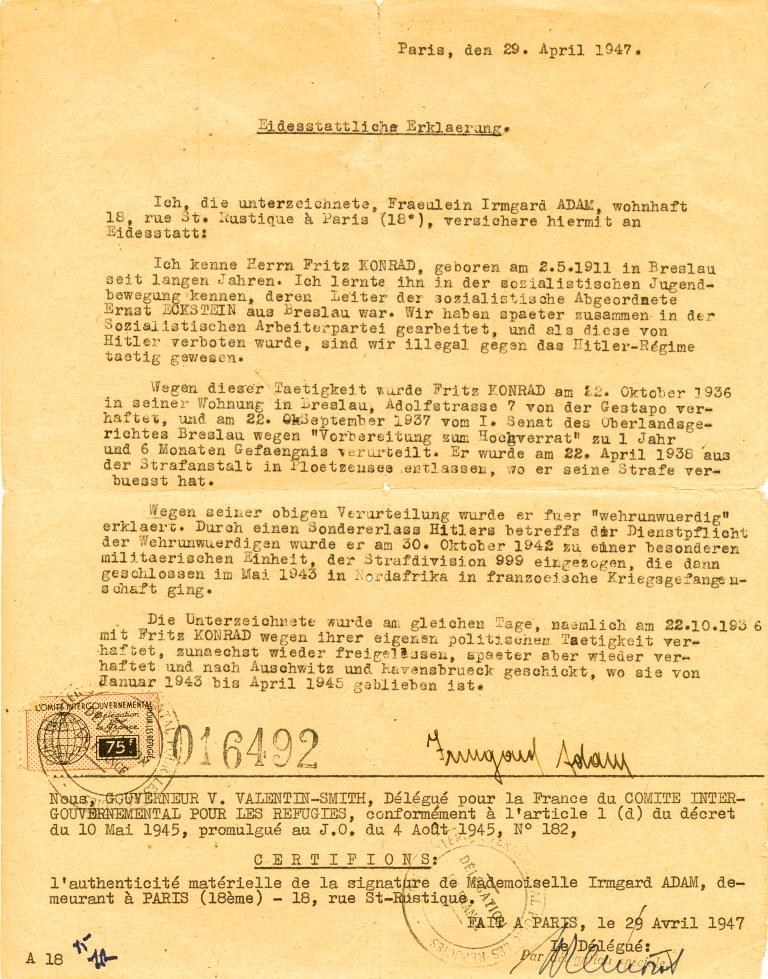

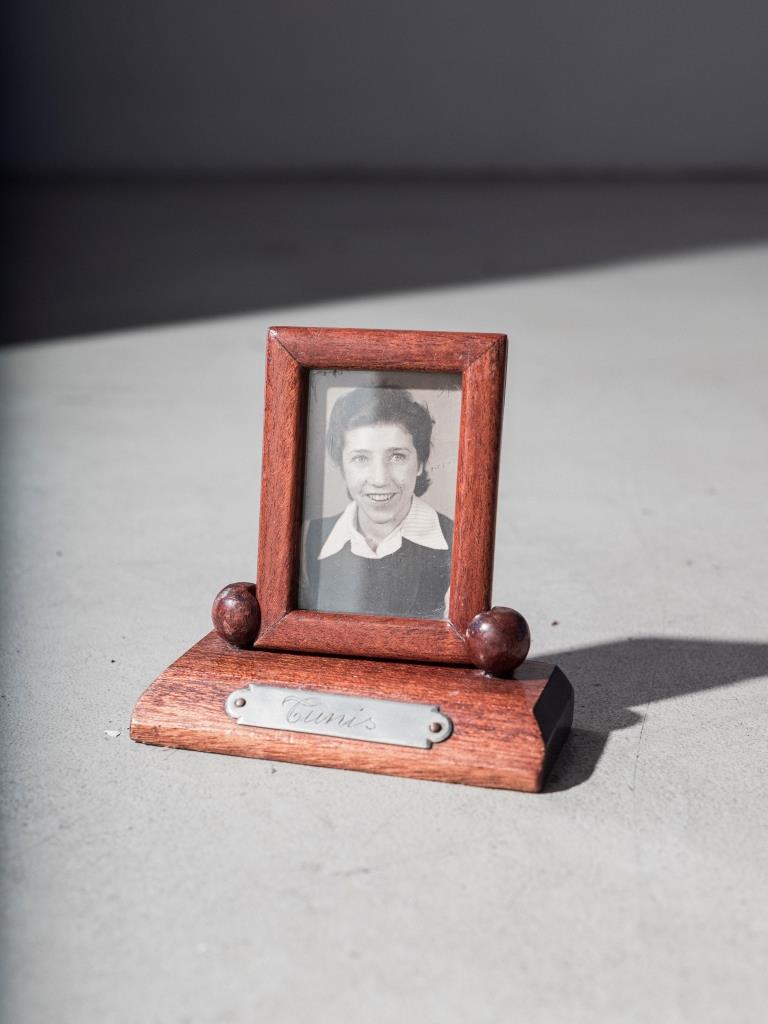

Born in 1915 in Breslau, Silesia, politicized in the socialist youth movement, active in resistance against the Nazis, she survived the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp, almost two years of forced labor for Siemens in the Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp, and the “death march” thanks to the solidarity of other prisoners. After the liberation by the Red Army, my grandmother went to France, hoping to find members of her family there. In Paris, she experienced for the first time again what a life in freedom feels like, only clouded by the uncertainty about the fate of her childhood love Fritz. Back in Germany in 1947 and finally reunited with him again after five years of separation, they both married 1948 in Leipzig/East Germany where she gave birth to a daughter, my mother.

Against the background of the biographies of my grandparents Irmgard Adam and Fritz Konrad I have been concerned for a while with the phenomenon of transgenerational traumatization researched in epigenetics. What is meant by this is the passing on of individually experienced traumas, which continue to have an effect over several years and which can reveal themselves in the self-image, in the emotional experience, in the unconscious action of future generations.

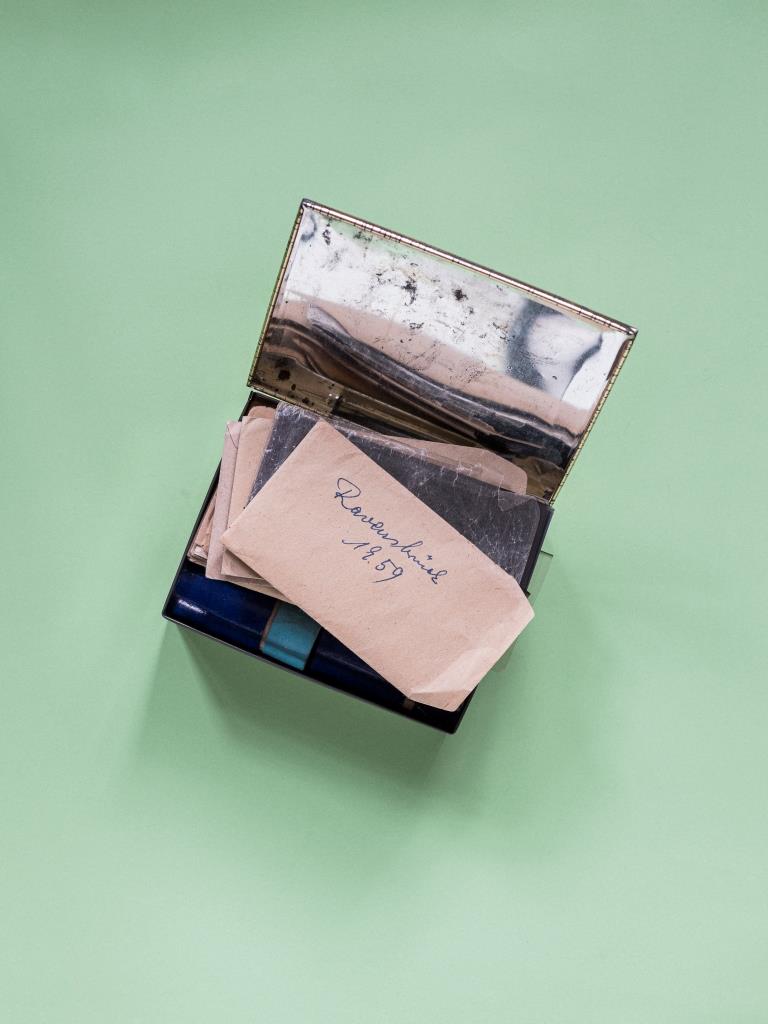

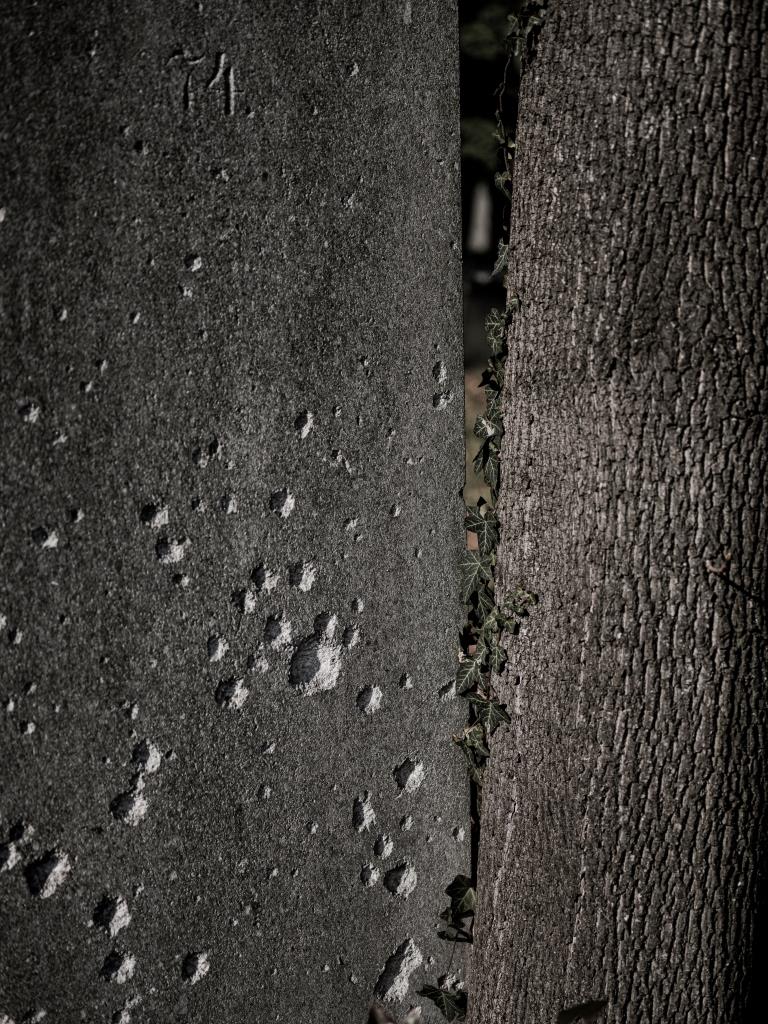

How much can we control the past within us? How much trauma experience of our ancestors is a part of us today? What does this mean for our generation and its descendants, what does it mean for myself? How important is it to know the biographies of our grandparents better? Inspired by the confrontation with my own identity, I came across photographs, letters, documents and interviews, traveled together with my mother to fateful places in my grandparent’s life.

I was looking for traces of their eventful life, with its incredibly difficult but also beautiful times. I look for them on the outside and I look for them on the inside, deep inside me.

RAUFASER is a photographic case study that uses my own documentary photography and archival material to investigate my ancestor’s history. With this work, I want to raise awareness of how the aftermath of war and crisis can affect the generations that follow and examine how collective and individual memory is shaped and influenced. Creating a new sense of identity by confronting myself with the past, spanning four generations, provides the basis for a detailed investigation of post-memory, mental health, war and history. My work RAUFASER is certainly very personal, however for me it is inseparably interwoven with the specific collective history as a German and European.

Daniel Seiffert was born in 1980. Before studying photography at Ostkreuz School for Photography in Berlin, he earned a Master ’s degree in Political Science, Communication and African Studies from universities in Berlin, Potsdam and Lisbon. Among others, he has received the prestigious C/O Talents Award and the Canon Award for Young Professional Photographers and was nominated for international FOAM Paul Huf Award. His work has been widely exhibited internationally, for example at C/O Berlin, ParisPHOTO, PhotoEspana. His book “Kraftwerk Jugend” was shortlisted for the Dummy Award of 5th International Photobook Award Kassel and has been part of book shows at Le Bal Paris and at the Brighton Photo Biennial. Since 2017 he has been part of the artist collective. As a happy father of two daughters he lives and works as a freelance photographer and picture editor in his hometown Berlin on commissioned and personal projects. ‘RAUFASER is a photographic case study that uses my own documentary photography and archival material to investigate my ancestors’ history. With this work, I want to raise awareness of how the aftermath of war and crisis can affect the generations that follow, and examine how collective and individual memory is shaped and influenced.’