Persephone was picking flowers when Hades eyed her and opened the earth to swallow her down to his underworld. It was done with her father’s approval of entitlement as a fellow ruler of realms, his right to pick the flowers he liked. Demeter, her mother (of all mothers, goddess of growth) despaired and the earth suffered with her, echoing her loss of child in its own sterility. Greed wintered the world, and a cycle of consequence was begun.

While her abduction spread mortal hunger all over, it was Persephone’s eating that changed everything. Pulled through a looking-glass boundary, she occupied another world that was both echo-chamber and shadow of what she had known. She was in the dark. She opened her mouth, tasted the fruit of the place she resided, swallowed six seeds that took root in her, and rooted her to their world.

By the relentless blood of motherhood and vegetation, Demeter dug out her daughter and Persephone was partly revived and recovered into sunlight. But her childhood name, Kore, unclaimed, was lost. A seal was broken in her as it had been in the ground she walked on. She was implanted by the logic of the plant, and would forever be Persephone: emergent, shooting-forth greenly then retreating back underground, the symbol of death that was coming.

Persephone contains all of the tensions of vegetative burgeoning, and all of the silence. Within her blossoming is death and the trauma of knowing it, within her return to the underworld is the seed of renewal. As a protagonist she is curiously obscured in the tellings of her tale. She is the site of conflict between the most primary of opponents: Hades and Demeter, power and protection, masculinity and motherhood, death and life. Their actions make desires explicit, Persephone the object fought over like plucked a flower.

Her desires are not, however, pantomimed like a debate. She is passive, passed between. Her only action is a different, silent act of tongue: she eats. And the sensuality of fruit-eating is foreshadowed by the olfactory delight of flower picking. As such in Persephone we find Eve, whose transgression is the opening of her mouth and enjoying (frui, fructus, fruit), intercoursing with what sprouts from a peculiar place of another’s power.

Shadowing Persephone is the myth of the ruinable woman, the hymen, the traversing of orifice as both claim and irreparable wound. And the violence is ultimate, and the damage irreparable. She is a definitive myth of rape and its consequence, to be read now as psychological, not only physical. Both body and entire world are traumatised by claiming-of-control, and it returns and returns.

But within the blur of Persephone is also potential for renewal. She represents fertility within the realm of the dead, glowing like a pomegranate seed. She represents both continuity and change, and is full of ambiguity. She is definitively adolescent – ultimately between places, between parents and sex, half in another world, dominated and split.

Persephone is a stolen child, and her pomegranate a reminder that the potential desires of ‘innocents’ is a significant dimension of Changeling-horror. It is the curiosity, the sensual delight, of other worlds that frightens us, that threatens to change people we ‘know’, we fear for and fear, where they might grow away on another temporal plane. Persephone’s transition redefines her, of course, as the bringer of destruction.

The O of Once upon a time becomes the hole she is pulled into becomes the emptiness she left becomes the circle of a seed becomes her open mouth becomes the wound of the irreversible becomes the cycle of repetition and renewal. Persephone roots and branches in many directions, as myths do, full of holes that fill with questions.

Hers is a story about a terrible violence and its consequence but, in tension and tandem, also potentially a story about empathy. Persephone breaks the surface, seeps between. The myth reminds us that we find ourselves in the world we inhabit, environmental and culture, but also find it echoing within us, understanding ourselves on its terms, and it on ours. We are always opening our mouths, letting out, letting in.

If the rape of Persephone and her victimhood is to be taken as prototype, it might seem easier, neater, to read her story as destruction of the purely innocent, because such a reading does nothing to disrupt belief in boundaries or the perfection of tragedy. It closes it away from the stickiness of realities and relations that is our social environment. But to diminish Persephone as such is to overlook the complexities of fruit and adolescence, and to limit mythology’s fertility as a ground on which to ask ourselves questions, creeping forward and retreating, finding slow cycles of potential growth.

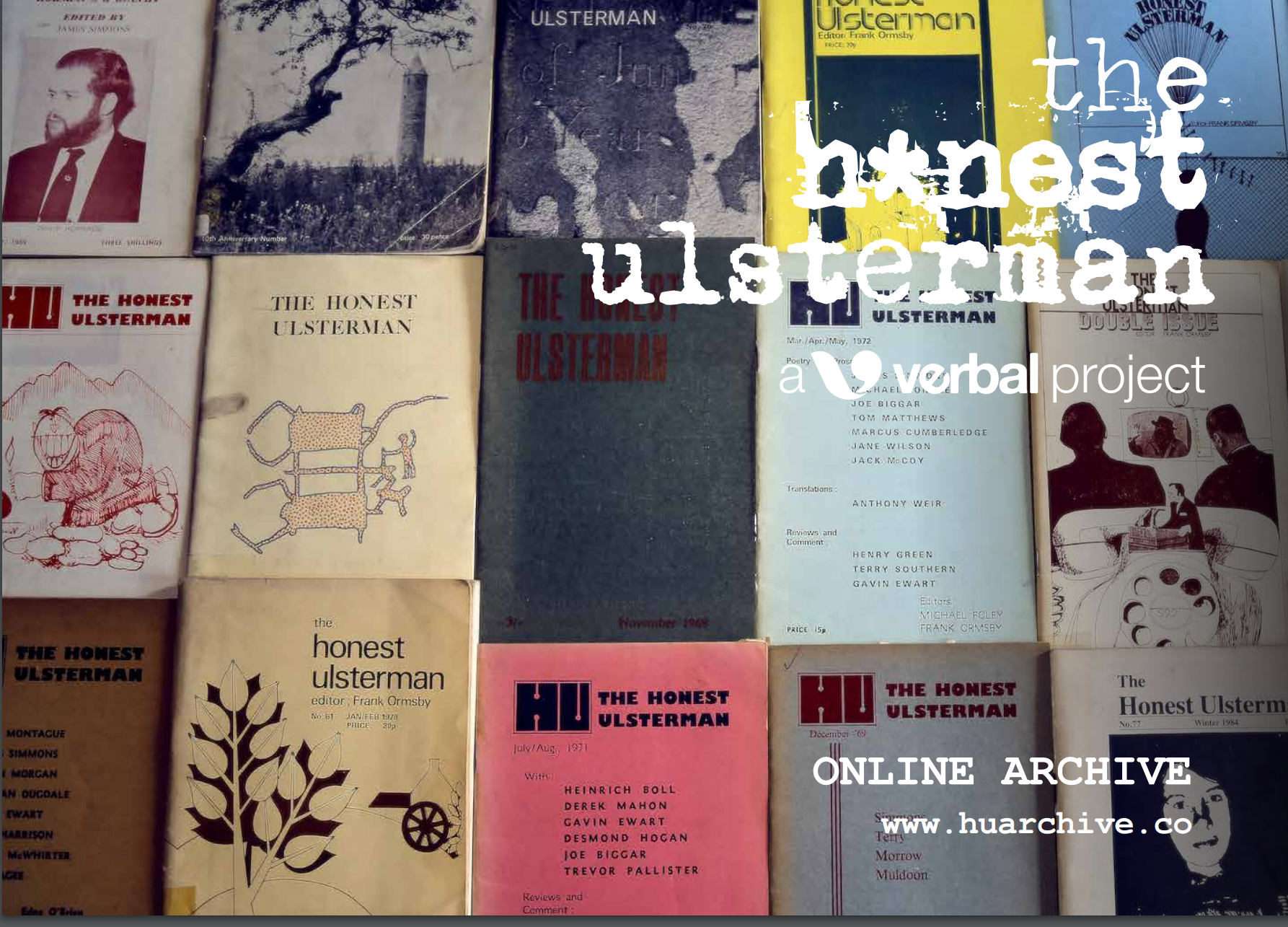

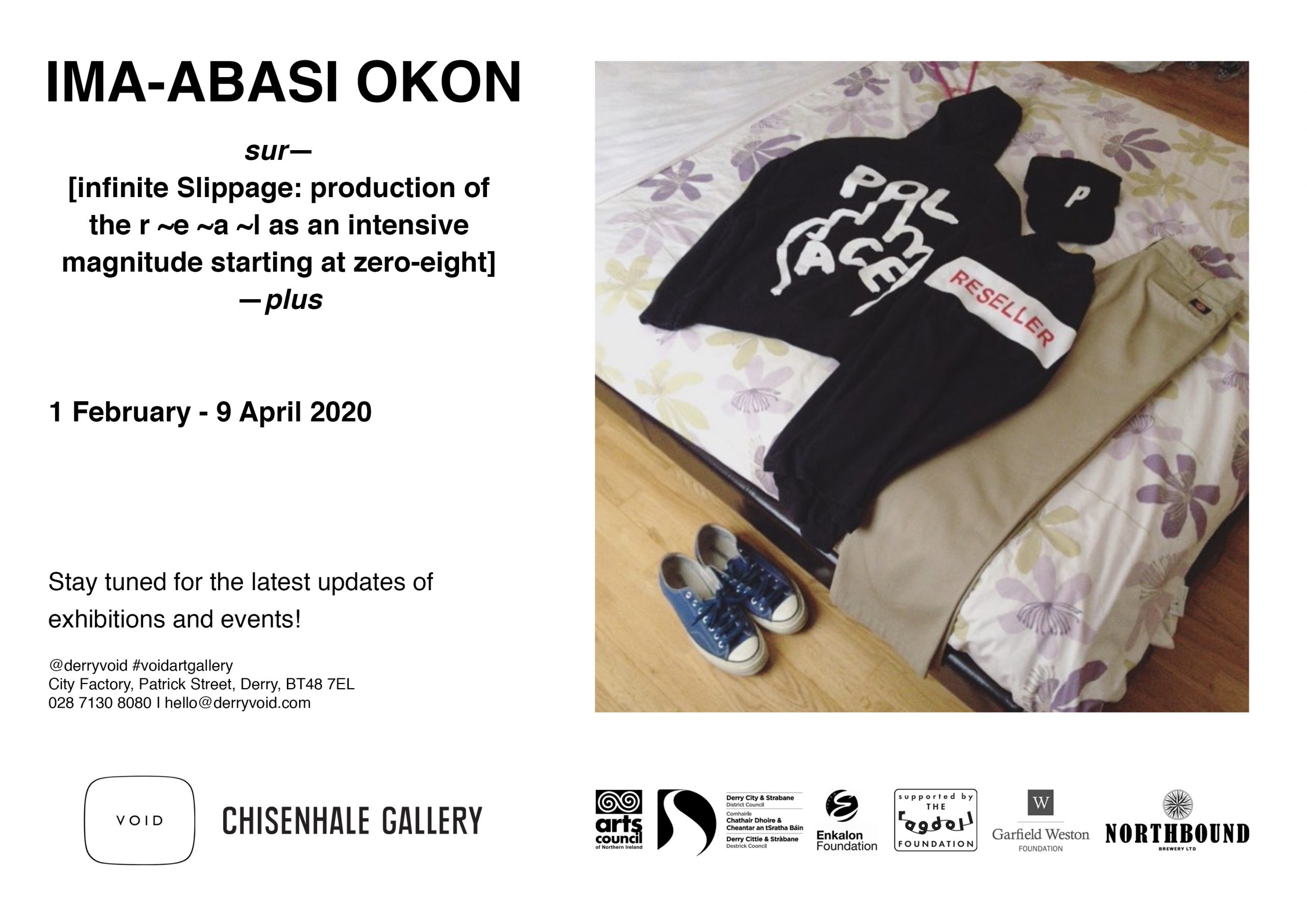

All art in this issue is by Megan Doherty, a photographer hailing from Derry, Northern Ireland. Since graduating from the University of Ulster, Belfast in 2016, Doherty continues to build upon her current body of work, embodying ideas of youth, subculture, freedom and escape. Doherty creates a darkly cinematic atmosphere to reflect the need for escapism within small-town life. In her native Derry, the Magnum Graduate Award shortlister creates a fictional, highly textured and colourful world in which recurring characters are played by friends. In her work, the scenarios are a combination of composed and documented, depicting the vibrant culture of young adulthood from a distinctly more female perspective. You can see more of her work at http://www.megandoherty.com.